Overview and Tutorial¶

Introduction¶

The lsqfit module is designed to facilitate least-squares fitting of

noisy data by multi-dimensional, nonlinear functions of arbitrarily many

parameters, each with a (Bayesian) prior. lsqfit makes heavy use of

another module, gvar (distributed separately), which provides tools

that simplify the analysis of error propagation, and also the creation of

complicated multi-dimensional Gaussian distributions.

This technology also allows lsqfit

to calculate exact derivatives of fit functions from the fit functions

themselves, using automatic differentiation, thereby avoiding the need to

code these by hand (the fitters use the derivatives).

The power of the

gvar module, particularly for correlated distributions, enables

a variety of unusual fitting strategies, as we illustrate below;

it is a feature that distinguishes lsqfit from

standard fitting packages.

The following (complete) code illustrates basic usage of lsqfit:

import numpy as np

import gvar as gv

import lsqfit

y = { # data for the dependent variable

'data1' : gv.gvar([1.376, 2.010], [[ 0.0047, 0.01], [ 0.01, 0.056]]),

'data2' : gv.gvar([1.329, 1.582], [[ 0.0047, 0.0067], [0.0067, 0.0136]]),

'b/a' : gv.gvar(2.0, 0.5)

}

x = { # independent variable

'data1' : np.array([0.1, 1.0]),

'data2' : np.array([0.1, 0.5])

}

prior = {}

prior['a'] = gv.gvar(0.5, 0.5)

prior['b'] = gv.gvar(0.5, 0.5)

def fcn(x, p): # fit function of x and parameters p

ans = {}

for k in ['data1', 'data2']:

ans[k] = gv.exp(p['a'] + x[k] * p['b'])

ans['b/a'] = p['b'] / p['a']

return ans

# do the fit

fit = lsqfit.nonlinear_fit(data=(x, y), prior=prior, fcn=fcn, debug=True)

print(fit.format(maxline=True)) # print standard summary of fit

p = fit.p # best-fit values for parameters

outputs = dict(a=p['a'], b=p['b'])

outputs['b/a'] = p['b']/p['a']

inputs = dict(y=y, prior=prior)

print(gv.fmt_values(outputs)) # tabulate outputs

print(gv.fmt_errorbudget(outputs, inputs)) # print error budget for outputs

This code fits the function f(x,a,b)= exp(a+b*x) (see fcn(x,p))

to two sets of data, labeled data1 and data2, by varying parameters

a and b until f(x['data1'],a,b) and f(x['data2'],a,b)

equal y['data1'] and y['data2'], respectively, to within the

ys’ errors.

The means and covariance matrices for the ys are

specified in the gv.gvar(...)s used to create them: thus, for example,

>>> print(y['data1'])

[1.376(69) 2.01(24)]

>>> print(y['data1'][0].mean, "+-", y['data1'][0].sdev)

1.376 +- 0.068556546004

>>> print(gv.evalcov(y['data1'])) # covariance matrix

[[ 0.0047 0.01 ]

[ 0.01 0.056 ]]

shows the means, standard deviations and covariance matrix for the data in the first data set (0.0685565 is the square root of the 0.0047 in the covariance matrix).

The dictionary prior gives a priori estimates

for the two parameters, a and b: each is assumed to be 0.5±0.5

before fitting. The parameters p[k] in the fit function fcn(x, p)

are stored in a dictionary having the same keys and layout as

prior (since prior specifies the fit parameters for

the fitter).

In addition to the data1 and data2 data sets,

there is an extra piece of input data,

y['b/a'], which indicates that b/a is 2±0.5. The fit

function for this data is simply the ratio b/a (represented by

p['b']/p['a'] in fit function fcn(x,p)). The fit function returns

a dictionary having the same keys and layout as the input data y.

The output from the code sample above is:

Least Square Fit:

chi2/dof [dof] = 0.17 [5] Q = 0.97 logGBF = 0.65538

Parameters:

a 0.253 (32) [ 0.50 (50) ]

b 0.449 (65) [ 0.50 (50) ]

Fit:

key y[key] f(p)[key]

---------------------------------------

b/a 2.00 (50) 1.78 (30)

data1 0 1.376 (69) 1.347 (46)

1 2.01 (24) 2.02 (16)

data2 0 1.329 (69) 1.347 (46)

1 1.58 (12) 1.612 (82)

Settings:

svdcut/n = 1e-12/0 tol = (1e-08*,1e-10,1e-10) (itns/time = 8/0.0)

Values:

a: 0.253(32)

b/a: 1.78(30)

b: 0.449(65)

Partial % Errors:

a b/a b

----------------------------------------

y: 12.75 16.72 14.30

prior: 0.92 1.58 1.88

----------------------------------------

total: 12.78 16.80 14.42

The best-fit values for a and b are 0.253(32) and

0.449(65), respectively; and the best-fit result for b/a is

1.78(30), which, because of correlations, is slightly more accurate

than might be expected from the separate errors for a and b. The

error budget for each of these three quantities is tabulated at the end and

shows that the bulk of the error in each case comes from uncertainties in

the y data, with only small contributions from uncertainties in the

priors prior. The fit results corresponding to each piece of input data

are also tabulated (Fit: ...); the agreement is excellent, as expected

given that the chi**2 per degree of freedom is only 0.17.

Note that the constraint in y on b/a in this example is much tighter

than the constraints on a and b separately. This suggests a variation

on the previous code, where the tight restriction on b/a is built into the

prior rather than y:

... as before ...

y = { # data for the dependent variable

'data1' : gv.gvar([1.376, 2.010], [[ 0.0047, 0.01], [ 0.01, 0.056]]),

'data2' : gv.gvar([1.329, 1.582], [[ 0.0047, 0.0067], [0.0067, 0.0136]])

}

x = { # independent variable

'data1' : np.array([0.1, 1.0]),

'data2' : np.array([0.1, 0.5])

}

prior = {}

prior['a'] = gv.gvar(0.5, 0.5)

prior['b'] = prior['a'] * gv.gvar(2.0, 0.5)

def fcn(x, p): # fit function of x and parameters p[k]

ans = {}

for k in ['data1', 'data2']:

ans[k] = gv.exp(p['a'] + x[k]*p['b'])

return ans

... as before ...

Here the dependent data y no longer has an entry for b/a, and neither

do results from the fit function; but the prior for b is now 2±0.5

times the prior for a, thereby introducing a correlation that

limits the ratio b/a to be 2±0.5 in the fit. This code gives almost

identical results to the first one — very slightly less accurate, since

there is slightly less input data. We can often move information

from the y data to

the prior or back since both are forms of input information.

There are several things worth noting from this example:

The input data (

y) is expressed in terms of Gaussian random variables — quantities with means and a covariance matrix. These are represented by objects of typegvar.GVarin the code; modulegvarhas a variety of tools for creating and manipulating Gaussian random variables (also see below).The input data is stored in a dictionary (

y) whose values can begvar.GVars or arrays ofgvar.GVars. The use of a dictionary allows for far greater flexibility than, say, an array. The fit function (fcn(x, p)) has to return a dictionary with the same layout as that ofy(that is, with the same keys and where the value for each key has the same shape as the corresponding value iny).lsqfitallowsyto be an array instead of a dictionary, which might be preferable for simple fits (but usually not otherwise).The independent data (

x) can be anything; it is simply passed through the fit code to the fit functionfcn(x,p). It can also be omitted altogether, in which case the fit function depends only upon the parameters:fcn(p).The fit parameters (

pinfcn(x,p)) are also stored in a dictionary whose values aregvar.GVars or arrays ofgvar.GVars. Again this allows for great flexibility. The layout of the parameter dictionary is copied from that of the prior (prior). Againpcan be a single array instead of a dictionary, if that simplifies the code.The best-fit values of the fit parameters (

fit.p[k]) are alsogvar.GVars and these capture statistical correlations between different parameters that are indicated by the fit. These output parameters can be combined in arithmetic expressions, using standard operators and standard functions, to obtain derived quantities. These operations take account of and track statistical correlations.Function

gvar.fmt_errorbudget()is a useful tool for assessing the origins (inputs) of the statistical errors obtained in various final results (outputs). It is particularly useful for analyzing the impact of the a priori uncertainties encoded in the prior (prior).Parameter

debug=Trueis set inlsqfit.nonlinear_fit. This is a good idea, particularly in the early stages of a project, because it causes the code to check for various common errors and give more intelligible error messages than would otherwise arise. This parameter can be dropped once code development is over.The priors for the fit parameters specify Gaussian distributions, characterized by the means and standard deviations given

gv.gvar(...). Some other distributions are available, and new ones can be created. The distribution for parametera, for example, can be switched to a log-normal distribution by replacingprior['a']=gv.gvar(0.5, 0.5)with:prior['log(a)'] = gv.log(gv.gvar(0.5,0.5))in the code. This change would be desirable, for example, if we knew a priori that parameter

ais positive since this is guaranteed with a log-normal distribution. Only the prior need be changed. (In particular, the fit functionfcn(x,p)need not be changed.)

What follows is a tutorial that demonstrates in greater detail how to use these modules in a selection of variations on the data fitting problem. As above, code for the examples is specified completely (with one exception) and so can be copied into a file, and run as is. It can also be modified, allowing for experimentation.

Another way to learn about the modules is to examine the case studies that follow this section. Each focuses on a single problem, again with the full code and data to allow for experimentation.

About Printing: The examples in this tutorial use the print function

as it is used in Python 3. Drop the outermost parenthesis in each print

statement if using Python 2; or add

from __future__ import print_function

at the start of your file.

Gaussian Random Variables and Error Propagation¶

The inputs and outputs of a nonlinear least squares analysis are probability

distributions, and these distributions will be Gaussian provided the input

data are sufficiently accurate. lsqfit assumes this to be the case.

(It also provides tests for non-Gaussian behavior, together with

methods for dealing with such behavior. See: Non-Gaussian Behavior; Testing Fits.)

One of the most distinctive features of lsqfit is that it is

built around a class, gvar.GVar, of objects that can be used to

represent arbitrarily complicated Gaussian distributions

— that is, they represent Gaussian random variables that specify the means and

covariance matrix of the probability distributions.

The input data for a fit are represented

by a collection of gvar.GVars that specify both the values and possible

errors in the input values. The result of a fit is a collection of

gvar.GVars specifying the best-fit values for the fit parameters and the

estimated uncertainties in those values.

gvar.GVars are defined in the gvar module.

There are five important things to know about them (see the

gvar documentation for more details):

gvar.GVars are created bygvar.gvar(), individually or in groups: for example,>>> import gvar as gv >>> print(gv.gvar(1.0, 0.1), gv.gvar('1.0 +- 0.2'), gv.gvar('1.0(4)')) 1.00(10) 1.00(20) 1.00(40) >>> print(gv.gvar([1.0, 1.0, 1.0], [0.1, 0.2, 0.41])) [1.00(10) 1.00(20) 1.00(41)] >>> print(gv.gvar(['1.0(1)', '1.0(2)', '1.00(41)'])) [1.00(10) 1.00(20) 1.00(41)] >>> print(gv.gvar(dict(a='1.0(1)', b=['1.0(2)', '1.0(4)']))) {'a': 1.00(10),'b': array([1.00(20), 1.00(40)], dtype=object)}

gvaruses the compact notation 1.234(22) to represent 1.234±0.022 — the digits in parentheses indicate the uncertainty in the rightmost corresponding digits quoted for the mean value. Very large (or small) numbers use a notation like 1.234(22)e+10.

gvar.GVars describe not only means and standard deviations, but also statistical correlations between different objects. For example, thegvar.GVars created by>>> import gvar as gv >>> a, b = gv.gvar([1, 1], [[0.01, 0.01], [0.01, 0.010001]]) >>> print(a, b) 1.00(10) 1.00(10)both have means of

1and standard deviations equal to or very close to0.1, but the ratiob/ahas a standard deviation that is 100x smaller:>>> print(b / a) 1.0000(10)This is because the covariance matrix specified for

aandbwhen they were created has large, positive off-diagonal elements:>>> print(gv.evalcov([a, b])) # covariance matrix [[ 0.01 0.01 ] [ 0.01 0.010001]]These off-diagonal elements imply that

aandbare strongly correlated, which means thatb/aorb-awill have much smaller uncertainties thanaorbseparately. The correlation coefficient foraandbis 0.99995:>>> print(gv.evalcorr([a, b])) # correlation matrix [[ 1. 0.99995] [ 0.99995 1. ]]

gvar.GVars can be used in arithmetic expressions or as arguments to pure-Python functions. The results are alsogvar.GVars. Covariances are propagated through these expressions following the usual rules, (automatically) preserving information about correlations. For example, thegvar.GVarsaandbabove could have been created using the following code:>>> import gvar as gv >>> a = gv.gvar(1, 0.1) >>> b = a + gv.gvar(0, 0.001) >>> print(a, b) 1.00(10) 1.00(10) >>> print(b / a) 1.0000(10) >>> print(gv.evalcov([a, b])) [[ 0.01 0.01 ] [ 0.01 0.010001]]The correlation is obvious from this code:

bis equal toaplus a very small correction. From these variables we can create new variables that are also highly correlated:>>> x = gv.log(1 + a ** 2) >>> y = b * gv.cosh(a / 2) >>> print(x, y, y / x) 0.69(10) 1.13(14) 1.627(34) >>> print gv.evalcov([x, y]) [[ 0.01 0.01388174] [ 0.01388174 0.01927153]]The

gvarmodule defines versions of the standard Python functions (sin,cos, …) that work withgvar.GVars. Most any numeric pure-Python function will work with them as well. Numeric functions that are compiled in C or other low-level languages generally do not work withgvar.GVars; they should be replaced by equivalent pure-Python functions if they are needed forgvar.GVar-valued arguments. See thegvardocumentation for more information.The fact that correlation information is preserved automatically through arbitrarily complicated arithmetic is what makes

gvar.GVars particularly useful. This is accomplished using automatic differentiation to compute the derivatives of any derivedgvar.GVarwith respect to the primarygvar.GVars (those defined usinggvar.gvar()) from which it was created. As a result, for example, we need not provide derivatives of fit functions forlsqfit(which are needed for the fit) since they are computed implicitly by the fitter from the fit function itself. Also it becomes trivial to build correlations into the priors used in fits, and to analyze the propagation of errors through complicated functions of the parameters after the fit.The uncertainties in derived

gvar.GVars come from the uncertainties in the primarygvar.GVars from which they were created. It is easy to create an “error budget” that decomposes the uncertainty in a derivedgvar.GVarinto components coming from each of the primarygvar.GVars involved in its creation. For example,>>> import gvar as gv >>> a = gv.gvar('1.0(1)') >>> b = gv.gvar('0.9(2)') >>> x = gv.log(1 + a ** 2) >>> y = b * gv.cosh(a / 2) >>> outputs = dict(x=x, y=y) >>> print(gv.fmt_values(outputs)) Values: y: 1.01(23) x: 0.69(10) >>> inputs = dict(a=a, b=b) >>> print(gv.fmt_errorbudget(outputs=outputs, inputs=inputs)) Partial % Errors: y x ------------------------------ a: 2.31 14.43 b: 22.22 0.00 ------------------------------ total: 22.34 14.43The error budget shows that most of

y’s 22.34% uncertainty comes fromb, with just 2.3% coming froma. The total uncertainty is the sum in quadrature of the two separate uncertainties. The uncertainty inxis entirely froma, of course.Storing

gvar.GVars in a file for later use is somewhat complicated because one generally wants to hold onto their correlations as well as their mean values and standard deviations. One easy way to do this is to put all of thegvar.GVars to be saved into a single array or dictionary that is saved using functiongvar.dump(): for example, use>>> gv.dump([a, b, x, y], 'outputfile.p')to save the variables defined above in a file named

'outputfile.p'. Loading the file into a Python code later, withgvar.load(), recovers the array with standard deviations and correlations intact:>>> a,b,x,y = gv.load('outputfile.p') >>> print(a, b, x, y) 1.00(10) 0.90(20) 0.69(10) 1.01(23) >>> print(y / b, gv.sqrt(gv.exp(x) - 1) / a) 1.128(26) 1(0)

gvar.dump()andgvar.load()are similar to the same functions in Python’spicklemodule, except that they can deal properly withgvar.GVars. They can be used to archive (possibly nested) containers like dictionaries and lists that containgvar.GVars (together with other data types), as well as many other types of object containinggvar.GVars. In particular, they can be used to save the best-fit parameters from a fit,>>> gv.dump(fit.p, 'fitpfile.p')or the entire

lsqfit.nonlinear_fitobject:>>> gv.dump(fit, 'fitfile.p')The archived fit preserves all or most of the fit object’s functionality (depending upon whether or not the fit function can be pickled): for example,

>>> fit = gv.load('fitfile.p') >>> print(fit) Least Square Fit: chi2/dof [dof] = 0.17 [5] Q = 0.97 logGBF = 0.65538 Parameters: a 0.253 (32) [ 0.50 (50) ] b 0.449 (65) [ 0.50 (50) ] Settings: svdcut/n = 1e-12/0 tol = (1e-08*,1e-10,1e-10) (itns/time = 8/0.0) >>> p = fit.p >>> outputs = dict(a=p['a'], b=p['b']) >>> outputs['b/a'] = p['b']/p['a'] >>> inputs = dict(y=y, prior=prior) >>> print(gv.fmt_errorbudget(outputs, inputs)) Partial % Errors: a b/a b ---------------------------------------- y: 12.75 16.72 14.30 prior: 0.92 1.58 1.88 ---------------------------------------- total: 12.78 16.80 14.42

There is considerably more information about gvar.GVars in the documentation

for module gvar.

Basic Fits¶

A fit analysis typically requires three types of input:

fit data

x,y(or possibly justy);a function

y = f(x,p)relating values ofyto values ofxand a set of fit parametersp; if there is nox, theny = f(p);some a priori idea about the fit parameters’ values (possibly quite imprecise — for example, that a particular parameter is of order 1).

The point of

the fit is to improve our knowledge of the parameter values, beyond

our a priori impressions, by analyzing the fit data. We now show how

to do this using the lsqfit module for a more realistic

problem, one that is

familiar from numerical simulations of quantum chromodynamics (QCD).

We need code for each of the three fit inputs. The fit data in our example is assembled by the following function:

import numpy as np

import gvar as gv

def make_data():

x = np.array([ 5., 6., 7., 8., 9., 10., 12., 14.])

ymean = np.array(

[ 4.5022829417e-03, 1.8170543788e-03, 7.3618847843e-04,

2.9872730036e-04, 1.2128831367e-04, 4.9256559129e-05,

8.1263644483e-06, 1.3415253536e-06]

)

ycov = np.array(

[[ 2.1537808808e-09, 8.8161794696e-10, 3.6237356558e-10,

1.4921344875e-10, 6.1492842463e-11, 2.5353714617e-11,

4.3137593878e-12, 7.3465498888e-13],

[ 8.8161794696e-10, 3.6193461816e-10, 1.4921610813e-10,

6.1633547703e-11, 2.5481570082e-11, 1.0540958082e-11,

1.8059692534e-12, 3.0985581496e-13],

[ 3.6237356558e-10, 1.4921610813e-10, 6.1710468826e-11,

2.5572230776e-11, 1.0608148954e-11, 4.4036448945e-12,

7.6008881270e-13, 1.3146405310e-13],

[ 1.4921344875e-10, 6.1633547703e-11, 2.5572230776e-11,

1.0632830128e-11, 4.4264622187e-12, 1.8443245513e-12,

3.2087725578e-13, 5.5986403288e-14],

[ 6.1492842463e-11, 2.5481570082e-11, 1.0608148954e-11,

4.4264622187e-12, 1.8496194125e-12, 7.7369196122e-13,

1.3576009069e-13, 2.3914810594e-14],

[ 2.5353714617e-11, 1.0540958082e-11, 4.4036448945e-12,

1.8443245513e-12, 7.7369196122e-13, 3.2498644263e-13,

5.7551104112e-14, 1.0244738582e-14],

[ 4.3137593878e-12, 1.8059692534e-12, 7.6008881270e-13,

3.2087725578e-13, 1.3576009069e-13, 5.7551104112e-14,

1.0403917951e-14, 1.8976295583e-15],

[ 7.3465498888e-13, 3.0985581496e-13, 1.3146405310e-13,

5.5986403288e-14, 2.3914810594e-14, 1.0244738582e-14,

1.8976295583e-15, 3.5672355835e-16]]

)

return x, gv.gvar(ymean, ycov)

The function call x,y = make_data() returns eight x[i], and the

corresponding values y[i] that we will fit. The y[i] are gvar.GVars

(Gaussian random variables — see previous section)

built from the mean values in ymean and the covariance matrix ycov, which shows strong correlations:

>>> print(y) # fit data

[0.004502(46) 0.001817(19) 0.0007362(79) ... 1.342(19)e-06]

>>> print(gv.evalcorr(y)) # correlation matrix

[[ 1. 0.99853801 0.99397698 ... 0.83814041]

[ 0.99853801 1. 0.99843828 ... 0.86234032]

[ 0.99397698 0.99843828 1. ... 0.88605708]

...

...

...

[ 0.83814041 0.86234032 0.88605708 ... 1. ]]

These particular data were generated numerically. They come from a function that is a sum of a very large number of decaying exponentials,

a[i] * np.exp(-E[i] * x)

with coefficients a[i] of order 0.5±0.4 and exponents E[i] of

order i+1±0.4. The function was evaluated with a particular set of

parameters a[i] and E[i], and then noise was added to create

this data. Our challenge is to find estimates for the values of the

parameters a[i] and E[i] that were used to create the data.

Next we need code for the fit function. Here we know that a sum of decaying exponentials is appropriate, and therefore we define the following Python function:

import numpy as np

def f(x, p): # function used to fit x, y data

a = p['a'] # array of a[i]s

E = p['E'] # array of E[i]s

return sum(ai * np.exp(-Ei * x) for ai, Ei in zip(a, E))

The fit parameters, a[i] and E[i], are stored as arrays in a

dictionary, using labels a and E to access them. These parameters

are varied in the fit to find the best-fit values p=fit.p for which

f(x,fit.p) most closely approximates the ys in our fit data. The

number of exponentials included in the sum is specified implicitly in this

function, by the lengths of the p['a'] and p['E'] arrays. In

principle there are infinitely many exponentials; in practice, given the

finite precision of our data, we will need only a few.

Finally we need to define priors that encapsulate our a priori knowledge

about the fit-parameter values. In practice we almost always have a priori

knowledge about parameters; it is usually impossible to design a fit

function without some sense of the parameter sizes. Given such knowledge

it is important (often essential) to include it in the fit. This is

done by designing priors for the fit, which are probability distributions

for each parameter that describe the a priori uncertainty in that

parameter. As discussed in the previous section, we use objects of type

gvar.GVar to describe (Gaussian) probability distributions.

Here we know that each a[i] is of order

0.5±0.4, while E[i] is of order 1+i±0.4. A prior

that represents this information is built using the following code:

import lsqfit

import gvar as gv

def make_prior(nexp): # make priors for fit parameters

prior = gv.BufferDict() # any dictionary works

prior['a'] = [gv.gvar(0.5, 0.4) for i in range(nexp)]

prior['E'] = [gv.gvar(i+1, 0.4) for i in range(nexp)]

return prior

where nexp is the number of exponential terms that will be used (and

therefore the number of a[i]s and E[i]s). With nexp=3,

for example, we have:

>>> print(prior['a'])

[0.50(40) 0.50(40) 0.50(40)]

>>> print(prior['E'])

[1.00(40), 2.00(40), 3.00(40)]

We habitually

use dictionary-like class gvar.BufferDict for the prior because it

allows for a variety of non-Gaussian priors (see Positive Parameters; Non-Gaussian Priors).

If non-Gaussian priors are unnecessary, gvar.BufferDict can be replaced by

dict() or most any other Python dictionary class.

With fit data, a fit function, and a prior for the fit parameters, we are finally ready to do the fit, which is now easy:

fit = lsqfit.nonlinear_fit(data=(x, y), fcn=f, prior=prior)

Our complete Python program is, therefore:

import lsqfit

import numpy as np

import gvar as gv

def main():

x, y = make_data() # collect fit data

p0 = None # make larger fits go faster (opt.)

for nexp in range(1, 7):

print('************************************* nexp =', nexp)

prior = make_prior(nexp)

fit = lsqfit.nonlinear_fit(data=(x, y), fcn=f, prior=prior, p0=p0)

print(fit) # print the fit results

if nexp > 2:

E = fit.p['E'] # best-fit parameters

a = fit.p['a']

print('E1/E0 =', E[1] / E[0], ' E2/E0 =', E[2] / E[0])

print('a1/a0 =', a[1] / a[0], ' a2/a0 =', a[2] / a[0])

if fit.chi2 / fit.dof < 1.:

p0 = fit.pmean # starting point for next fit (opt.)

print()

# error budget analysis

outputs = {

'E1/E0':E[1]/E[0], 'E2/E0':E[2]/E[0],

'a1/a0':a[1]/a[0], 'a2/a0':a[2]/a[0]

}

inputs = {'E':fit.prior['E'], 'a':fit.prior['a'], 'y':y}

print('================= Error Budget Analysis')

print(gv.fmt_values(outputs))

print(gv.fmt_errorbudget(outputs,inputs))

def f(x, p): # function used to fit x, y data

a = p['a'] # array of a[i]s

E = p['E'] # array of E[i]s

return sum(ai * np.exp(-Ei * x) for ai, Ei in zip(a, E))

def make_prior(nexp): # make priors for fit parameters

prior = gv.BufferDict() # any dictionary works

prior['a'] = [gv.gvar(0.5, 0.4) for i in range(nexp)]

prior['E'] = [gv.gvar(i+1, 0.4) for i in range(nexp)]

return prior

def make_data(): # assemble fit data

x = np.array([ 5., 6., 7., 8., 9., 10., 12., 14.])

ymean = np.array(

[ 4.5022829417e-03, 1.8170543788e-03, 7.3618847843e-04,

2.9872730036e-04, 1.2128831367e-04, 4.9256559129e-05,

8.1263644483e-06, 1.3415253536e-06]

)

ycov = np.array(

[[ 2.1537808808e-09, 8.8161794696e-10, 3.6237356558e-10,

1.4921344875e-10, 6.1492842463e-11, 2.5353714617e-11,

4.3137593878e-12, 7.3465498888e-13],

[ 8.8161794696e-10, 3.6193461816e-10, 1.4921610813e-10,

6.1633547703e-11, 2.5481570082e-11, 1.0540958082e-11,

1.8059692534e-12, 3.0985581496e-13],

[ 3.6237356558e-10, 1.4921610813e-10, 6.1710468826e-11,

2.5572230776e-11, 1.0608148954e-11, 4.4036448945e-12,

7.6008881270e-13, 1.3146405310e-13],

[ 1.4921344875e-10, 6.1633547703e-11, 2.5572230776e-11,

1.0632830128e-11, 4.4264622187e-12, 1.8443245513e-12,

3.2087725578e-13, 5.5986403288e-14],

[ 6.1492842463e-11, 2.5481570082e-11, 1.0608148954e-11,

4.4264622187e-12, 1.8496194125e-12, 7.7369196122e-13,

1.3576009069e-13, 2.3914810594e-14],

[ 2.5353714617e-11, 1.0540958082e-11, 4.4036448945e-12,

1.8443245513e-12, 7.7369196122e-13, 3.2498644263e-13,

5.7551104112e-14, 1.0244738582e-14],

[ 4.3137593878e-12, 1.8059692534e-12, 7.6008881270e-13,

3.2087725578e-13, 1.3576009069e-13, 5.7551104112e-14,

1.0403917951e-14, 1.8976295583e-15],

[ 7.3465498888e-13, 3.0985581496e-13, 1.3146405310e-13,

5.5986403288e-14, 2.3914810594e-14, 1.0244738582e-14,

1.8976295583e-15, 3.5672355835e-16]]

)

return x, gv.gvar(ymean, ycov)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

We are not sure a priori how many exponentials are needed to fit our

data. Consequently

we write our code to try fitting with each of nexp=1,2,3..6 terms.

(The pieces of the code involving p0 are optional; they make the

more complicated fits go about 30 times faster since the output from one

fit is used as the starting point for the next fit — see the discussion

of the p0 parameter for lsqfit.nonlinear_fit.) Running

this code produces the following output, which is reproduced here in some

detail in order to illustrate a variety of features:

************************************* nexp = 1

Least Square Fit:

chi2/dof [dof] = 1.2e+03 [8] Q = 0 logGBF = -4837.2

Parameters:

a 0 0.00735 (59) [ 0.50 (40) ] *

E 0 1.1372 (49) [ 1.00 (40) ]

Settings:

svdcut/n = 1e-12/1 tol = (1e-08*,1e-10,1e-10) (itns/time = 12/0.0)

************************************* nexp = 2

Least Square Fit:

chi2/dof [dof] = 2.2 [8] Q = 0.024 logGBF = 111.69

Parameters:

a 0 0.4024 (40) [ 0.50 (40) ]

1 0.4471 (46) [ 0.50 (40) ]

E 0 0.90104 (51) [ 1.00 (40) ]

1 1.8282 (14) [ 2.00 (40) ]

Settings:

svdcut/n = 1e-12/1 tol = (1e-08*,1e-10,1e-10) (itns/time = 9/0.0)

************************************* nexp = 3

Least Square Fit:

chi2/dof [dof] = 0.63 [8] Q = 0.76 logGBF = 116.29

Parameters:

a 0 0.4019 (40) [ 0.50 (40) ]

1 0.406 (14) [ 0.50 (40) ]

2 0.61 (36) [ 0.50 (40) ]

E 0 0.90039 (54) [ 1.00 (40) ]

1 1.8026 (82) [ 2.00 (40) ]

2 2.83 (19) [ 3.00 (40) ]

Settings:

svdcut/n = 1e-12/1 tol = (1e-08*,1e-10,1e-10) (itns/time = 28/0.0)

E1/E0 = 2.0020(86) E2/E0 = 3.14(21)

a1/a0 = 1.011(32) a2/a0 = 1.52(89)

************************************* nexp = 4

Least Square Fit:

chi2/dof [dof] = 0.63 [8] Q = 0.76 logGBF = 116.3

Parameters:

a 0 0.4019 (40) [ 0.50 (40) ]

1 0.406 (14) [ 0.50 (40) ]

2 0.61 (36) [ 0.50 (40) ]

3 0.50 (40) [ 0.50 (40) ]

E 0 0.90039 (54) [ 1.00 (40) ]

1 1.8026 (82) [ 2.00 (40) ]

2 2.83 (19) [ 3.00 (40) ]

3 4.00 (40) [ 4.00 (40) ]

Settings:

svdcut/n = 1e-12/1 tol = (1e-08*,1e-10,1e-10) (itns/time = 9/0.0)

E1/E0 = 2.0020(86) E2/E0 = 3.14(21)

a1/a0 = 1.011(32) a2/a0 = 1.52(89)

************************************* nexp = 5

Least Square Fit:

chi2/dof [dof] = 0.63 [8] Q = 0.76 logGBF = 116.3

Parameters:

a 0 0.4019 (40) [ 0.50 (40) ]

1 0.406 (14) [ 0.50 (40) ]

2 0.61 (36) [ 0.50 (40) ]

3 0.50 (40) [ 0.50 (40) ]

4 0.50 (40) [ 0.50 (40) ]

E 0 0.90039 (54) [ 1.00 (40) ]

1 1.8026 (82) [ 2.00 (40) ]

2 2.83 (19) [ 3.00 (40) ]

3 4.00 (40) [ 4.00 (40) ]

4 5.00 (40) [ 5.00 (40) ]

Settings:

svdcut/n = 1e-12/1 tol = (1e-08*,1e-10,1e-10) (itns/time = 4/0.0)

E1/E0 = 2.0020(86) E2/E0 = 3.14(21)

a1/a0 = 1.011(32) a2/a0 = 1.52(89)

************************************* nexp = 6

Least Square Fit:

chi2/dof [dof] = 0.63 [8] Q = 0.76 logGBF = 116.3

Parameters:

a 0 0.4019 (40) [ 0.50 (40) ]

1 0.406 (14) [ 0.50 (40) ]

2 0.61 (36) [ 0.50 (40) ]

3 0.50 (40) [ 0.50 (40) ]

4 0.50 (40) [ 0.50 (40) ]

5 0.50 (40) [ 0.50 (40) ]

E 0 0.90039 (54) [ 1.00 (40) ]

1 1.8026 (82) [ 2.00 (40) ]

2 2.83 (19) [ 3.00 (40) ]

3 4.00 (40) [ 4.00 (40) ]

4 5.00 (40) [ 5.00 (40) ]

5 6.00 (40) [ 6.00 (40) ]

Settings:

svdcut/n = 1e-12/1 tol = (1e-08*,1e-10,1e-10) (itns/time = 2/0.0)

E1/E0 = 2.0020(86) E2/E0 = 3.14(21)

a1/a0 = 1.011(32) a2/a0 = 1.52(89)

================= Error Budget Analysis

Values:

E1/E0: 2.0020(86)

E2/E0: 3.14(21)

a1/a0: 1.011(32)

a2/a0: 1.52(89)

Partial % Errors:

E1/E0 E2/E0 a1/a0 a2/a0

--------------------------------------------------

a: 0.07 5.47 0.82 52.75

E: 0.12 3.23 1.04 25.36

y: 0.40 2.08 2.78 5.24

--------------------------------------------------

total: 0.43 6.72 3.15 58.78

There are several things to notice here:

Clearly two exponentials (

nexp=2) are not sufficient. Thechi**2per degree of freedom (chi2/dof) is significantly larger than one. Thechi**2improves substantially fornexp=3exponentials, and there is essentially no change when further exponentials are added.The best-fit values for each parameter are listed for each of the fits, together with the prior values (in brackets, on the right). Values for each

a[i]andE[i]are listed in order, starting at the points indicated by the labelsaandE. Asterisks are printed at the end of the line if the mean best-fit value differs from the prior’s mean by more than one standard deviation (seenexp=1); the number of asterisks, up to a maximum of 5, indicates how many standard deviations the difference is. Differences of one or two standard deviations are not uncommon; larger differences could indicate a problem with the data, prior, or fit function.Once the fit converges, the best-fit values for the various parameters agree well — that is to within their errors, approximately — with the exact values, which we know since we made the data. For example,

aandEfor the first exponential are 0.402(4) and 0.9004(5), respectively, from the fit, while the exact answers are 0.4 and 0.9; and we get 0.406(14) and 1.803(8) for the second exponential where the exact values are 0.4 and 1.8.Note in the fit with

nexp=4how the mean and standard deviation for the parameters governing the fourth (and last) exponential are identical to the values in the corresponding priors: 0.50(40) from the fit foraand 4.0(4) forE. This tells us that our fit data have no information to add to what we knew a priori about these parameters — there isn’t enough data and what we have isn’t accurate enough.This situation remains true of further terms as they are added in the

nexp=5and later fits. This is why the fit results stop changing once we havenexp=3exponentials. There is no point in including further exponentials, beyond the need to verify that the fit has indeed converged. Note that the underlying function from which the data came had 100 exponential terms.The last fit includes

nexp=6exponentials and therefore has 12 parameters. This is in a fit to 8ys. Old-fashioned fits, without priors, are impossible when the number of parameters exceeds the number of data points. That is clearly not the case here, where the number of terms and parameters can be made arbitrarily large, eventually (afternexp=3terms) with no effect at all on the results.The reason is that the prior that we include for each new parameter is, in effect, a new piece of data (equal to the mean and standard deviation of the a priori expectation for that parameter). Each prior leads to a new term in the

chi**2function; we are fitting both the data and our a priori expectations for the parameters. So in thenexp=6fit, for example, we actually have 20 pieces of data to fit: the 8ys plus the 12 prior values for the 12 parameters.That priors are additional fit data becomes obvious if we rewrite our fit function as

def g(x, p): # function used to fit x, y data a = p['a'] # array of a[i]s E = p['E'] # array of E[i]s return dict( y=sum(ai * np.exp(-Ei * x) for ai, Ei in zip(a, E)), a=a, E=E, )and add the following right after the loop in the

main()function:print('************************************* nexp =', nexp, '(fit g(x,p))') data = (x, dict(y=y, a=prior['a'], E=prior['E'])) gfit = lsqfit.nonlinear_fit(data=data, fcn=g, prior=None, p0=p0) print(gfit) print()This gives exactly the same results as the last fit from the loop, but now with the prior explicitly built into the fit function and data. This way of implementing priors, although equivalent, is generally less convenient.

The effective number of degrees of freedom (

dofin the output above) is the number of pieces of data minus the number of fit parameters, or 20-12=8 in this last case. With priors for every parameter, the number of degrees of freedom is always equal to the number ofys, irrespective of how many fit parameters there are.The Gaussian Bayes Factor (whose logarithm is

logGBFin the output) is a measure of the likelihood that the actual data being fit could have come from a theory with the prior and fit function used in the fit. The larger this number, the more likely it is that the prior/fit-function and data could be related. Here it grows dramatically from the first fit (nexp=1) but then stops changing afternexp=3. The implication is that these data are much more likely to have come from a theory withnexp>=3than one withnexp=1.In the code, results for each fit are captured in a Python object

fit, which is of typelsqfit.nonlinear_fit. A summary of the fit information is obtained by printingfit. Also the best-fit results for each fit parameter can be accessed throughfit.p, as is done here to calculate various ratios of parameters.The errors in these ratios automatically account for any correlations in the statistical errors for different parameters. This is evident in the ratio

a1/a0, which would be 1.010(35) if there was no statistical correlation between our estimates fora1anda0, but in fact is 1.010(31) in this fit. The modest (positive) correlation is clear from the correlation matrix:>>> print(gv.evalcorr(fit.p['a'][:2])) [[ 1. 0.36353303] [ 0.36353303 1. ]]After the last fit, the code uses function

gvar.fmt_errorbudgetto create an error budget. This requires dictionaries of fit inputs and outputs, and uses the dictionary keys to label columns and rows, respectively, in the error budget table. The table shows, for example, that the 0.43% uncertainty inE1/E0comes mostly from the fit data (0.40%), with small contributions from the uncertainties in the priors foraandE(0.07% and 0.12%, respectively). The total uncertainty is the sum in quadrature of these errors. This breakdown suggests that reducing the errors inyby 25% might reduce the error inE1/E0to around 0.3% (and it does). The uncertainty inE2/E0, on the other hand, comes mostly from the priors and is less likely to improve (it doesn’t).

Finally we inspect the fit’s quality point by point. The input data are

compared with results from the fit function, evaluated with the best-fit

parameters, in the following table (obtained in the code by printing the

output from fit.format(maxline=True)):

Fit:

x[k] y[k] f(x[k],p)

-----------------------------------------------

5 0.004502 (46) 0.004506 (46)

6 0.001817 (19) 0.001819 (19)

7 0.0007362 (79) 0.0007373 (78)

8 0.0002987 (33) 0.0002993 (32)

9 0.0001213 (14) 0.0001216 (13)

10 0.00004926 (57) 0.00004941 (56)

12 8.13(10)e-06 8.160(96)e-06

14 1.342(19)e-06 1.348(17)e-06

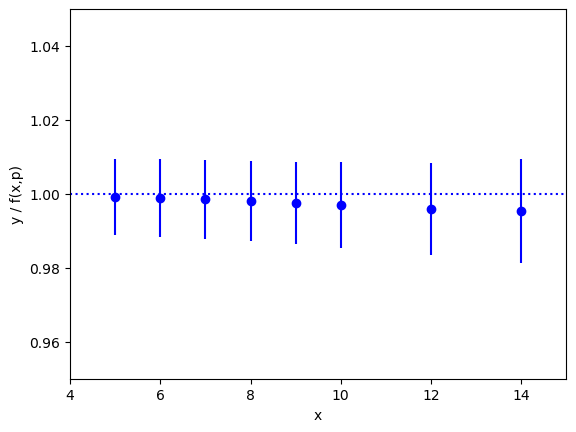

The fit is excellent over the entire three orders of magnitude. This

information is presented again in the following plot, which shows the ratio

y/f(x,p), as a function of x, using the best-fit parameters p.

The correct result for this ratio, of course, is one. The smooth variation

in the data — smooth compared with the size of the statistical-error bars

— is an indication of the statistical correlations between individual

ys.

This particular plot was made using the matplotlib module, with the

following code added to the end of main() (outside the loop):

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

ratio = y / f(x, fit.pmean)

plt.xlim(4, 15)

plt.ylim(0.95, 1.05)

plt.xlabel('x')

plt.ylabel('y / f(x,p)')

plt.errorbar(x=x, y=gv.mean(ratio), yerr=gv.sdev(ratio), fmt='ob')

plt.plot([4.0, 21.0], [1.0, 1.0], 'b:')

plt.show()

Chained Fits; Large Data Sets¶

The priors in a fit represent knowledge that we have about the parameters before we do the fit. This knowledge might come from theoretical considerations or experiment. Or it might come from another fit. Here we look at two examples that exploit the possibility of chaining fits, where the output of one fit is an input (the prior) to another.

Imagine first that we want to add new information to that extracted from the

fit in the previous section. For example, we might learn from some other

source that the ratio of amplitudes a[1]/a[0] equals 1±1e-5. The challenge

is to combine this new information with information extracted from the fit

above without rerunning that fit. (We assume it is not possible to rerun.)

We can combine the new data with the old fit results by creating a new

fit that uses the best-fit parameters, fit.p, from the old fit as its

prior. To try this out, we modify

the main() function in the previous section, adding the new fit at the

end:

def main():

x, y = make_data() # collect fit data

p0 = None # make larger fits go faster (opt.)

for nexp in range(1, 5):

prior = make_prior(nexp)

fit = lsqfit.nonlinear_fit(data=(x, y), fcn=fcn, prior=prior, p0=p0)

if fit.chi2 / fit.dof < 1.:

p0 = fit.pmean # starting point for next fit (opt.)

# print nexp=4 fit results

print('--------------------- original fit')

print(fit)

E = fit.p['E'] # best-fit parameters

a = fit.p['a']

print('E1/E0 =', E[1] / E[0], ' E2/E0 =', E[2] / E[0])

print('a1/a0 =', a[1] / a[0], ' a2/a0 =', a[2] / a[0])

# new fit adds new data about a[1] / a[0]

def ratio(p): # new fit function

a = p['a']

return a[1] / a[0]

prior = fit.p # prior = best-fit parameters from nexp=4 fit

data = gv.gvar(1, 1e-5) # new data for the ratio

newfit = lsqfit.nonlinear_fit(data=data, fcn=ratio, prior=prior)

print('\n--------------------- new fit to extra information')

print(newfit)

E = newfit.p['E']

a = newfit.p['a']

print('E1/E0 =', E[1] / E[0], ' E2/E0 =', E[2] / E[0])

print('a1/a0 =', a[1] / a[0], ' a2/a0 =', a[2] / a[0])

The results of the new fit (to one piece of new data) are at the end of the output:

--------------------- original fit

Least Square Fit:

chi2/dof [dof] = 0.63 [8] Q = 0.76 logGBF = 116.3

Parameters:

a 0 0.4019 (40) [ 0.50 (40) ]

1 0.406 (14) [ 0.50 (40) ]

2 0.61 (36) [ 0.50 (40) ]

3 0.50 (40) [ 0.50 (40) ]

E 0 0.90039 (54) [ 1.00 (40) ]

1 1.8026 (82) [ 2.00 (40) ]

2 2.83 (19) [ 3.00 (40) ]

3 4.00 (40) [ 4.00 (40) ]

Settings:

svdcut/n = 1e-12/1 tol = (1e-08*,1e-10,1e-10) (itns/time = 4/0.0)

E1/E0 = 2.0020(86) E2/E0 = 3.14(21)

a1/a0 = 1.011(32) a2/a0 = 1.52(89)

--------------------- new fit to extra information

Least Square Fit:

chi2/dof [dof] = 0.12 [1] Q = 0.73 logGBF = 2.4648

Parameters:

a 0 0.4018 (40) [ 0.4019 (40) ]

1 0.4018 (40) [ 0.406 (14) ]

2 0.57 (34) [ 0.61 (36) ]

3 0.50 (40) [ 0.50 (40) ]

E 0 0.90033 (51) [ 0.90039 (54) ]

1 1.7998 (13) [ 1.8026 (81) ]

2 2.79 (14) [ 2.83 (19) ]

3 4.00 (40) [ 4.00 (40) ]

Settings:

svdcut/n = 1e-12/0 tol = (1e-08*,1e-10,1e-10) (itns/time = 14/0.0)

E1/E0 = 1.9991(12) E2/E0 = 3.10(16)

a1/a0 = 1.000000(10) a2/a0 = 1.43(85)

Parameters a[0] and E[0] are essentially unchanged by the new

information, but a[1] and E[1] are much more precise,

as is a[1]/a[0], of course.

It might seem odd that E[1], for example, is changed at

all, since the fit function, ratio(p), makes no mention of it. This

is not surprising, however, since ratio(p) does depend upon a[1],

and a[1] is strongly correlated with E[1] through the prior

(correlation coefficient of 0.94).

It is important to include all parameters from the first fit as

parameters in the new fit, in order to capture the impact of the new

information on parameters correlated with a[1]/a[0].

Obviously, we can use further fits in order to incorporate additional data. The

prior for each new fit is the best-fit output (fit.p) from the previous

fit. The output from the chain’s final fit is the cumulative result of all

of these fits.

Note that this particular problem can be done much more

simply using a weighted average (lsqfit.wavg()).

Adding the following code

onto the end of the main() function above

fit.p['a1/a0'] = fit.p['a'][1] / fit.p['a'][0]

new_data = {'a1/a0' : gv.gvar(1,1e-5)}

new_p = lsqfit.wavg([fit.p, new_data])

print('chi2/dof = {:.2f}\n' .format(new_p.chi2 / new_p.dof))

print('E:', new_p['E'][:4])

print('a:', new_p['a'][:4])

print('a1/a0:', new_p['a1/a0'])

gives the following output:

chi2/dof = 0.12

E: [0.90033(51) 1.7998(13) 2.79(14) 4.00(40)]

a: [0.4018(40) 0.4018(40) 0.57(34) 0.50(40)]

a1/a0: 1.000000(10)

Here we do a weighted average of a[1]/a[0] from the

original fit (fit.p['a1/a0']) with our new piece of data

(new_data['a1/a0']). The dictionary new_p returned by

lsqfit.wavg() has an entry for

every key in either fit.p or new_data. The weighted average for

a[1]/a[0] is in new_p['a1/a0']. New values for the

fit parameters, that take account of the new data, are stored in

new_p['E'] and new_p['a']. The E[i] and a[i]

estimates differ from their values in fit.p since those parameters

are correlated with a[1]/a[0]. Consequently when the ratio

is shifted by new data, the E[i] and a[i] are shifted as well.

The final results in new_p

are identical to what we obtained above.

One place where chained fits can be useful is when there is lots of fit

data. Imagine, as a second example, a situation that involves 10,000 highly

correlated y[i]s. A straight fit would take a very long time because

part of the fit process involves diagonalizing the fit data’s (dense)

10,000×10,000 covariance matrix. Instead we break the data up into

batches of 100 and do chained fits of one batch after another:

# read data from disk

x, y = read_data()

print('x = [{} {} ... {}]'.format(x[0], x[1], x[-1]))

print('y = [{} {} ... {}]'.format(y[0], y[1], y[-1]))

print('corr(y[0],y[9999]) =', gv.evalcorr([y[0], y[-1]])[1,0])

print()

# fit function and prior

def fcn(x, p):

return p[0] + p[1] * np.exp(- p[2] * x)

prior = gv.gvar(['0(1)', '0(1)', '0(1)'])

# Nstride fits, each to nfit data points

nfit = 100

Nstride = len(y) // nfit

fit_time = 0.0

for n in range(0, Nstride):

fit = lsqfit.nonlinear_fit(

data=(x[n::Nstride], y[n::Nstride]), prior=prior, fcn=fcn

)

prior = fit.p

if n in [0, 9]:

print('******* Results from ', (n+1) * nfit, 'data points')

print(fit)

print('******* Results from ', Nstride * nfit, 'data points (final)')

print(fit)

In the loop, we fit only 100 data points at a time, but the prior we use is the best-fit result from the fit to the previous 100 data points, and its prior comes from fitting the 100 points before those, and so on for 100 fits in all. The output from this code is:

x = [0.2 0.200080008001 ... 1.0]

y = [0.836(10) 0.835(10) ... 0.686(10)]

corr(y[0],y[9999]) = 0.990099009901

******* Results from 100 data points

Least Square Fit:

chi2/dof [dof] = 1.1 [100] Q = 0.23 logGBF = 523.92

Parameters:

0 0.494 (13) [ 0.0 (1.0) ]

1 0.3939 (75) [ 0.0 (1.0) ]

2 0.715 (23) [ 0.0 (1.0) ]

Settings:

svdcut/n = 1e-12/0 tol = (1e-08*,1e-10,1e-10) (itns/time = 11/0.1)

******* Results from 1000 data points

Least Square Fit:

chi2/dof [dof] = 1.1 [100] Q = 0.29 logGBF = 544.96

Parameters:

0 0.491 (10) [ 0.492 (10) ]

1 0.3969 (24) [ 0.3965 (25) ]

2 0.7084 (70) [ 0.7095 (74) ]

Settings:

svdcut/n = 1e-12/0 tol = (1e-08*,1e-10,1e-10) (itns/time = 6/0.0)

******* Results from 10000 data points (final)

Least Square Fit:

chi2/dof [dof] = 1 [100] Q = 0.48 logGBF = 548.63

Parameters:

0 0.488 (10) [ 0.488 (10) ]

1 0.39988 (77) [ 0.39982 (78) ]

2 0.7002 (23) [ 0.7003 (23) ]

Settings:

svdcut/n = 1e-12/0 tol = (1e-08*,1e-10,1e-10) (itns/time = 4/0.4)

It shows the errors on p[1] and p[2] decreasing steadily as more

data points are included. The error on p[0], however, hardly changes

at all. This is a consequence of the strong correlation between different

y[i]s (and its lack of x-dependence).

The “correct” answers here are 0.5, 0.4 and 0.7.

Chained fits are slower that straight fits with large amounts of

uncorrelated data, provided lsqfit.nonlinear_fit is informed ahead of

time that the data are uncorrelated (by default it checks for

correlations, which can be expensive for lots of data).

The fitter is informed by using argument

udata instead of data to specify the fit data:

x, y = read_data()

print('x = [{} {} ... {}]'.format(x[0], x[1], x[-1]))

print('y = [{} {} ... {}]'.format(y[0], y[1], y[-1]))

print()

# fit function and prior

def fcn(x, p):

return p[0] + p[1] * np.exp(- p[2] * x)

prior = gv.gvar(['0(1)', '0(1)', '0(1)'])

fit = lsqfit.nonlinear_fit(udata=(x, y), prior=prior, fcn=fcn)

print(fit)

Using udata rather than data causes lsqfit.nonlinear_fit to

ignore correlations in the data, whether they exist or not.

Uncorrelated fits are typically

much faster when fitting large amounts of data, so it is then

possible to fit much more data

(e.g., 1,000,000 or more y[i]s is straightforward on a laptop).

x has Errors¶

We now consider variations on our basic fit analysis (described in

Basic Fits).

The first variation concerns what to do when the independent variables, the

xs, have errors, as well as the ys. This is easily handled by

turning the xs into fit parameters, and otherwise dispensing

with independent variables.

To illustrate, consider the data assembled by the following make_data

function:

import gvar as gv

def make_data():

x = gv.gvar([

'0.73(50)', '2.25(50)', '3.07(50)', '3.62(50)', '4.86(50)',

'6.41(50)', '6.39(50)', '7.89(50)', '9.32(50)', '9.78(50)',

'10.83(50)', '11.98(50)', '13.37(50)', '13.84(50)', '14.89(50)'

])

y = gv.gvar([

'3.85(70)', '5.5(1.7)', '14.0(2.6)', '21.8(3.4)', '47.0(5.2)',

'79.8(4.6)', '84.9(4.6)', '95.2(2.2)', '97.65(79)', '98.78(55)',

'99.41(25)', '99.80(12)', '100.127(77)', '100.202(73)', '100.203(71)'

])

return x,y

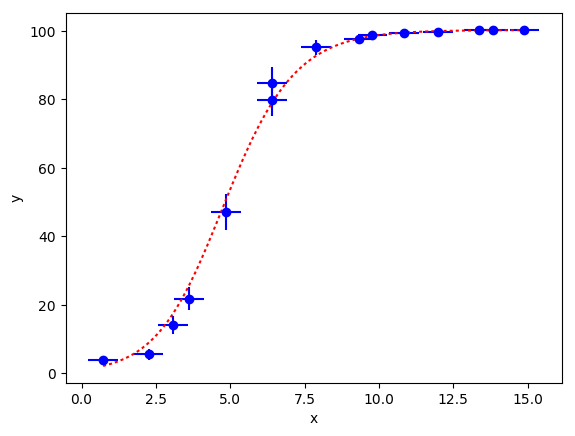

The function call x,y = make_data() returns values for the x[i]s and

the corresponding y[i]s, where now both are gvar.GVars.

We want to fit the y values with a function of the form:

b0 / ((1 + gv.exp(b1 - b2 * x)) ** (1. / b3)).

So we have two sets of parameters for which we need priors: the b[i]s and

the x[i]s:

import gvar as gv

def make_prior(x):

prior = gv.BufferDict()

prior['b'] = gv.gvar(['0(500)', '0(5)', '0(5)', '0(5)'])

prior['x'] = x

return prior

The prior values for the x[i] are just the values returned by

make_data(). The corresponding fit function is:

import gvar as gv

def fcn(p):

b0, b1, b2, b3 = p['b']

x = p['x']

return b0 / ((1. + gv.exp(b1 - b2 * x)) ** (1. / b3))

where the dependent variables x[i] are no longer arguments

of the function,

but rather are fit parameter in dictionary p.

The actual fit is now straightforward:

import lsqfit

x, y = make_data()

prior = make_prior(x)

fit = lsqfit.nonlinear_fit(prior=prior, data=y, fcn=fcn)

print(fit)

This generates the following output:

Least Square Fit:

chi2/dof [dof] = 0.35 [15] Q = 0.99 logGBF = -40.156

Parameters:

b 0 100.238 (60) [ 0 (500) ]

1 3.5 (1.2) [ 0.0 (5.0) ]

2 0.797 (87) [ 0.0 (5.0) ]

3 0.77 (35) [ 0.0 (5.0) ]

x 0 1.26 (41) [ 0.73 (50) ] *

1 1.87 (34) [ 2.25 (50) ]

2 2.84 (28) [ 3.07 (50) ]

3 3.42 (29) [ 3.62 (50) ]

4 4.72 (32) [ 4.86 (50) ]

5 6.45 (33) [ 6.41 (50) ]

6 6.69 (35) [ 6.39 (50) ]

7 8.15 (36) [ 7.89 (50) ]

8 9.30 (35) [ 9.32 (50) ]

9 9.91 (37) [ 9.78 (50) ]

10 10.77 (37) [ 10.83 (50) ]

11 11.70 (38) [ 11.98 (50) ]

12 13.34 (46) [ 13.37 (50) ]

13 13.91 (48) [ 13.84 (50) ]

14 14.88 (50) [ 14.89 (50) ]

Settings:

svdcut/n = 1e-12/0 tol = (1e-08*,1e-10,1e-10) (itns/time = 13/0.1)

The fit gives new results for the b[i] parameters that are much

improved from our prior estimates. Results for many of the x[i]s

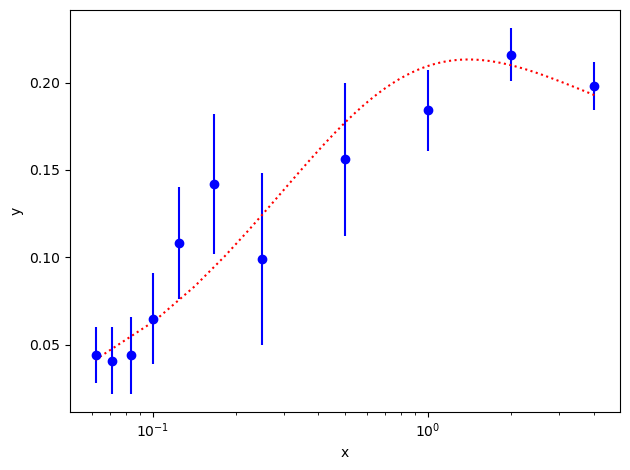

are improved as well, by information from the fit data. The following

plot shows the fit (dashed line) compared with the input data for y:

In practice, it is possible that the uncertainties in the x[i] are correlated

with those in the y[i]. It such cases the x[i] cannot be considered to be

prior information. The approach desribed above is still valid, however,

because lsqfit.nonlinear_fit checks for correlations between the data and

the priors, and includes them in the fit when they are present.

y has No Error; Marginalization¶

Occasionally there are fit problems where values for the dependent

variable y are known exactly (to machine precision). This poses a

problem for least-squares fitting since the chi**2 function is

infinite when standard deviations are zero. How does one assign errors

to exact ys in order to define a chi**2 function that can be

usefully minimized?

It is almost always the case in physical applications of this sort that the

fit function has in principle an infinite number of parameters. It is, of

course, impossible to extract information about infinitely many parameters

from a finite number of ys. In practice, however, we generally care about

only a few of the parameters in the fit function.

The goal for a least-squares fit is to figure out what a finite

number of exact ys can tell us about the parameters we want to know.

The key idea here is to use priors to model the part of the fit function that we don’t care about, and to remove that part of the function from the analysis by subtracting it out from the input data. This is called marginalization.

To illustrate how it is done, we consider data that is generated from an infinite sum of decaying exponentials, like that in Basic Fits:

import numpy as np

def make_data():

x = np.array([ 1., 1.2, 1.4, 1.6, 1.8, 2., 2.2, 2.4, 2.6])

y = np.array([

0.2740471001620033, 0.2056894154005132, 0.158389402324004,

0.1241967645280511, 0.0986901274726867, 0.0792134506060024,

0.0640743982173861, 0.052143504367789 , 0.0426383022456816,

])

return x, y

Now x,y = make_data() returns nine x[i]s together with the

corresponding y[i]s, but where the y[i]s are exact and so

no longer represented by gvar.GVars.

We want to fit these data with a sum of exponentials, as before:

import numpy as np

def fcn(x,p):

a = p['a'] # array of a[i]s

E = p['E'] # array of E[i]s

return np.sum(ai * np.exp(-Ei*x) for ai, Ei in zip(a, E))

We know that the amplitudes a[i] are of order 0.5±0.5, and

that the leading exponent E[0] is 1±0.1, as are the differences

between subsequent exponents dE[i] = E[i] - E[i-1]. This a priori

knowledge is encoded in the priors:

import numpy as np

import gvar as gv

def make_prior(nexp):

prior = gv.BufferDict()

prior['a'] = gv.gvar(nexp * ['0.5(5)'])

dE = gv.gvar(nexp * ['1.0(1)'])

prior['E'] = np.cumsum(dE)

return prior

We use a large number of exponential terms since

our y[i]s are exact: we keep 100 terms in all,

but our results are unchanged

with any number greater than about 10. Only a small number nexp

of these are included in the fit function. The 100-nexp terms left out

are subtracted from the y[i] before the fit, using

the prior values for the omitted parameters to evaluate these terms.

This gives

new fit data ymod[i]:

prior = make_prior(100)

# the first nexp terms are fit; the remainder go into ymod

fit_prior = gv.BufferDict()

ymod_prior = gv.BufferDict()

for k in prior:

fit_prior[k] = prior[:nexp]

ymod_prior[k] = prior[nexp:]

ymod = y - fcn(x, ymod_prior)

fit = lsqfit.nonlinear_fit(data=(x, ymod), prior=fit_prior, fcn=fcn)

By subtracting fcn(x, ymod_prior) from y, we remove the parameters

that are in ymod_prior from the data, and consequently those parameters

need not be included in fit function. The fitter uses only

the parameters left in fit_prior.

Our complete code, therefore, is:

import numpy as np

import gvar as gv

import lsqfit

def main():

x, y = make_data()

prior = make_prior(100) # 100 exponential terms in all

p0 = None

for nexp in range(1, 6):

# marginalize the last 100 - nexp terms (in ymod_prior)

fit_prior = gv.BufferDict() # part of prior used in fit

ymod_prior = gv.BufferDict() # part of prior absorbed in ymod

for k in prior:

fit_prior[k] = prior[k][:nexp]

ymod_prior[k] = prior[k][nexp:]

ymod = y - fcn(x, ymod_prior) # remove temrs in ymod_prior

# fit modified data with just nexp terms (in fit_prior)

fit = lsqfit.nonlinear_fit(

data=(x, ymod), prior=fit_prior, fcn=fcn, p0=p0, tol=1e-10,

)

# print fit information

print('************************************* nexp =',nexp)

print(fit.format(True))

p0 = fit.pmean

# print summary information and error budget

E = fit.p['E'] # best-fit parameters

a = fit.p['a']

outputs = {

'E1/E0':E[1] / E[0], 'E2/E0':E[2] / E[0],

'a1/a0':a[1] / a[0], 'a2/a0':a[2] / a[0]

}

inputs = {

'E prior':prior['E'], 'a prior':prior['a'],

'svd cut':fit.correction,

}

print(gv.fmt_values(outputs))

print(gv.fmt_errorbudget(outputs, inputs))

def fcn(x,p):

a = p['a'] # array of a[i]s

E = p['E'] # array of E[i]s

return np.sum(ai * np.exp(-Ei*x) for ai, Ei in zip(a, E))

def make_prior(nexp):

prior = gv.BufferDict()

prior['a'] = gv.gvar(nexp * ['0.5(5)'])

dE = gv.gvar(nexp * ['1.0(1)'])

prior['E'] = np.cumsum(dE)

return prior

def make_data():

x = np.array([ 1., 1.2, 1.4, 1.6, 1.8, 2., 2.2, 2.4, 2.6])

y = np.array([

0.2740471001620033, 0.2056894154005132, 0.158389402324004 ,

0.1241967645280511, 0.0986901274726867, 0.0792134506060024,

0.0640743982173861, 0.052143504367789 , 0.0426383022456816,

])

return x, y

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

We loop over nexp, moving parameters from ymod back into the fit

as nexp increases. The output from this script is:

************************************* nexp = 1

Least Square Fit:

chi2/dof [dof] = 0.19 [9] Q = 0.99 logGBF = 79.803

Parameters:

a 0 0.4067 (32) [ 0.50 (50) ]

E 0 0.9030 (16) [ 1.00 (10) ]

Fit:

x[k] y[k] f(x[k],p)

----------------------------------------

1 0.167 (74) 0.1648 (10)

1.2 0.141 (49) 0.13760 (82)

1.4 0.118 (32) 0.11487 (65)

1.6 0.099 (22) 0.09589 (51)

1.8 0.082 (14) 0.08004 (40)

2 0.0686 (97) 0.06682 (31)

2.2 0.0572 (65) 0.05578 (24)

2.4 0.0476 (44) 0.04656 (19)

2.6 0.0397 (30) 0.03887 (15)

Settings:

svdcut/n = 1e-12/2 tol = (1e-10*,1e-10,1e-10) (itns/time = 11/0.0)

************************************* nexp = 2

Least Square Fit:

chi2/dof [dof] = 0.19 [9] Q = 1 logGBF = 81.799

Parameters:

a 0 0.4015 (23) [ 0.50 (50) ]

1 0.435 (24) [ 0.50 (50) ]

E 0 0.9007 (11) [ 1.00 (10) ]

1 1.830 (28) [ 2.00 (14) ] *

Fit:

x[k] y[k] f(x[k],p)

------------------------------------------

1 0.235 (28) 0.2330 (27)

1.2 0.186 (15) 0.1847 (17)

1.4 0.1484 (81) 0.1474 (10)

1.6 0.1190 (44) 0.11833 (63)

1.8 0.0960 (24) 0.09552 (38)

2 0.0778 (13) 0.07749 (23)

2.2 0.06331 (74) 0.06313 (14)

2.4 0.05173 (41) 0.051624 (84)

2.6 0.04242 (23) 0.042351 (50)

Settings:

svdcut/n = 1e-12/2 tol = (1e-10*,1e-10,1e-10) (itns/time = 27/0.0)

************************************* nexp = 3

Least Square Fit:

chi2/dof [dof] = 0.2 [9] Q = 0.99 logGBF = 83.077

Parameters:

a 0 0.4011 (18) [ 0.50 (50) ]

1 0.426 (28) [ 0.50 (50) ]

2 0.468 (56) [ 0.50 (50) ]

E 0 0.90045 (77) [ 1.00 (10) ]

1 1.822 (27) [ 2.00 (14) ] *

2 2.84 (12) [ 3.00 (17) ]

Fit:

x[k] y[k] f(x[k],p)

--------------------------------------------

1 0.260 (10) 0.2593 (22)

1.2 0.1998 (45) 0.1995 (11)

1.4 0.1559 (20) 0.15576 (54)

1.6 0.12316 (91) 0.12305 (27)

1.8 0.09824 (41) 0.09818 (13)

2 0.07902 (19) 0.078988 (62)

2.2 0.063990 (85) 0.063973 (30)

2.4 0.052106 (38) 0.052098 (14)

2.6 0.042622 (17) 0.0426176 (68)

Settings:

svdcut/n = 1e-12/3 tol = (1e-10*,1e-10,1e-10) (itns/time = 64/0.0)

************************************* nexp = 4

Least Square Fit:

chi2/dof [dof] = 0.21 [9] Q = 0.99 logGBF = 83.212

Parameters:

a 0 0.4009 (10) [ 0.50 (50) ]

1 0.424 (22) [ 0.50 (50) ]

2 0.469 (61) [ 0.50 (50) ]

3 0.426 (94) [ 0.50 (50) ]

E 0 0.90036 (44) [ 1.00 (10) ]

1 1.819 (19) [ 2.00 (14) ] *

2 2.83 (11) [ 3.00 (17) ]

3 3.83 (15) [ 4.00 (20) ]

Fit:

x[k] y[k] f(x[k],p)

----------------------------------------------

1 0.2687 (38) 0.26843 (95)

1.2 0.2039 (14) 0.20376 (39)

1.4 0.15778 (51) 0.15771 (16)

1.6 0.12399 (19) 0.123955 (63)

1.8 0.098616 (69) 0.098603 (25)

2 0.079187 (26) 0.079182 (10)

2.2 0.0640650 (96) 0.0640627 (39)

2.4 0.0521401 (36) 0.0521392 (15)

2.6 0.0426371 (13) 0.04263670 (61)

Settings:

svdcut/n = 1e-12/3 tol = (1e-10*,1e-10,1e-10) (itns/time = 140/0.1)

************************************* nexp = 5

Least Square Fit:

chi2/dof [dof] = 0.21 [9] Q = 0.99 logGBF = 83.28

Parameters:

a 0 0.4009 (10) [ 0.50 (50) ]

1 0.424 (22) [ 0.50 (50) ]

2 0.468 (62) [ 0.50 (50) ]

3 0.42 (11) [ 0.50 (50) ]

4 0.45 (18) [ 0.50 (50) ]

E 0 0.90036 (43) [ 1.00 (10) ]

1 1.819 (19) [ 2.00 (14) ] *

2 2.83 (11) [ 3.00 (17) ]

3 3.83 (15) [ 4.00 (20) ]

4 4.83 (18) [ 5.00 (22) ]

Fit:

x[k] y[k] f(x[k],p)

-----------------------------------------------

1 0.2721 (14) 0.27196 (64)

1.2 0.20516 (42) 0.20510 (21)

1.4 0.15824 (13) 0.158219 (68)

1.6 0.124154 (38) 0.124147 (22)

1.8 0.098678 (12) 0.0986752 (70)

2 0.0792099 (36) 0.0792090 (23)

2.2 0.0640734 (11) 0.06407305 (85)

2.4 0.05214320 (33) 0.05214310 (40)

2.6 0.04263821 (10) 0.04263818 (27)

Settings:

svdcut/n = 1e-12/3 tol = (1e-10*,1e-10,1e-10) (itns/time = 248/0.1)

Values:

E2/E0: 3.15(12)

E1/E0: 2.021(20)

a2/a0: 1.17(15)

a1/a0: 1.057(52)

Partial % Errors:

E2/E0 E1/E0 a2/a0 a1/a0

--------------------------------------------------

E prior: 3.87 0.86 12.10 4.51

svd cut: 0.04 0.04 0.33 0.16

a prior: 0.84 0.47 5.33 1.92

--------------------------------------------------

total: 3.96 0.98 13.23 4.90

Here we use fit.format(True) to print out a table of x and

y (actually ymod) values, together with the value of the

fit function using the best-fit parameters. There are several things

to notice:

Even the

nexp=1fit, where we fit the data with just a single exponential, gives results for the two parameters that are accurate to 1% or better. The results don’t change much as further terms are shifted fromymodto the fit function, and stop changing completely bynexp=4.In fact it is straightforward to prove that best-fit parameter means and standard deviations, as well as

chi**2, should be exactly the same in such situations provided the fit function is linear in all fit parameters. Here the fit function is approximately linear, given our small standard deviations, and so results are only approximately independent ofnexp.

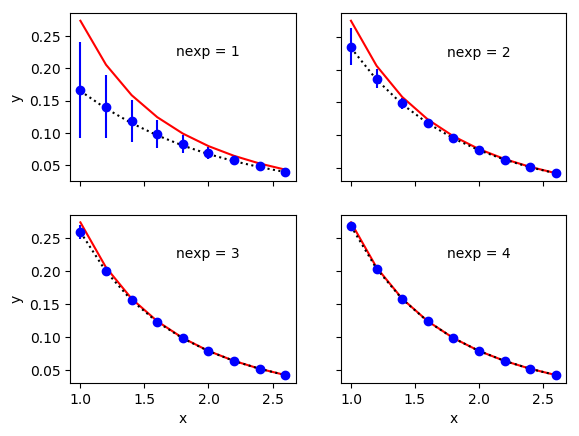

ymodhas large uncertainties whennexpis small, because of the uncertainties in the priors used to evaluatefcn(x, ymod_prior). This is clear from the following plots:

The solid lines in these plot show the exact results, from

yin the code. The dashed lines show the fit function with the best-fit parameters for thenexpterms used in each fit, and the data points showymod— these last two agree well, as expected from the excellentchi**2values. The uncertainties in differentymod[i]s are highly correlated with each other because they come from the same priors (inymod_prior). These correlations are evident in the plots and are essential to this procedure.Although we motivated this example by the need to deal with

ys having no errors, it is straightforward to apply the same ideas to a situation where theys have errors. Often in a fit we are interested in only one or two of many fit parameters. Getting rid of the uninteresting parameters (by absorbing them intoymod) can greatly reduce the number of parameters varied by the fit, thereby speeding up the fit. Here we are in effect doing a 100-exponential fit to our data, but actually fitting with only a handful of parameters (only 2 fornexp=1). The parameters removed in this way are said to be marginalized.

SVD Cuts and Roundoff Error¶

All of the fits discussed above have (default) SVD cuts of 1e-12. This has little impact in most of the problems, but makes a big difference in the problem discussed in the previous section. Had we run that fit, for example, with an SVD cut of 1e-19, instead of 1e-12, we would have obtained the following output:

************************************* nexp = 5

Least Square Fit:

chi2/dof [dof] = 0.21 [9] Q = 0.99 logGBF = 85.403

Parameters:

a 0 0.4009 (10) [ 0.50 (50) ]

1 0.424 (22) [ 0.50 (50) ]

2 0.469 (62) [ 0.50 (50) ]

3 0.42 (11) [ 0.50 (50) ]

4 0.46 (18) [ 0.50 (50) ]

E 0 0.90036 (43) [ 1.00 (10) ]

1 1.819 (19) [ 2.00 (14) ] *

2 2.83 (11) [ 3.00 (17) ]

3 3.83 (15) [ 4.00 (20) ]

4 4.83 (18) [ 5.00 (22) ]

Fit:

x[k] y[k] f(x[k],p)

-------------------------------------------

1 0.2721 (14) 0.272 (69)

1.2 0.20516 (42) 0.205 (57)

1.4 0.15824 (13) 0.158 (40)

1.6 0.124154 (38) 0.124 (27)

1.8 0.098678 (12) 0.099 (18)

2 0.0792099 (36) 0.079 (11)

2.2 0.0640734 (11) 0.0641 (70)

2.4 0.05214320 (33) 0.0521 (43)

2.6 0.04263821 (10) 0.0426 (25)

Settings:

svdcut/n = 1e-19/0 tol = (1e-10*,1e-10,1e-10) (itns/time = 309/0.1)

Values:

E2/E0: 3.1(2.7)

E1/E0: 2.02(45)

a2/a0: 1.2(5.3)

a1/a0: 1.1(1.4)

Partial % Errors:

E2/E0 E1/E0 a2/a0 a1/a0

--------------------------------------------------

E prior: 54.30 8.06 256.81 56.39

svd cut: 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00

a prior: 67.92 20.58 376.32 124.24

--------------------------------------------------

total: 86.96 22.10 455.59 136.44

The standard deviations quoted for E1/E0, etc. are much too large

compared with the standard deviations than what we obtained

in the previous section.

This is due to roundoff error. The strong correlations between the

different data points (ymod[i] — see the previous section) in this

analysis result

in a data covariance matrix that is too ill-conditioned without an SVD cut.

The inverse of the data’s covariance matrix is used in the chi**2

function that is minimized by lsqfit.nonlinear_fit. Given the

finite precision of computer hardware, it is impossible to compute this

inverse accurately if the matrix is almost singular, and in

such situations the reliability of the fit results is in question. The

eigenvalues of the covariance matrix in this example (for nexp=5)

cover a range of about 18 orders of magnitude — too large

to be handled in normal double precision computation.

The smallest eigenvalues and their

eigenvectors are likely to be quite inaccurate.

A standard solution to this common problem in least-squares fitting is

to introduce an SVD cut, here called svdcut:

fit = nonlinear_fit(data=(x, ymod), fcn=f, prior=prior, p0=p0, svdcut=1e-12)

This regulates the singularity of the covariance matrix by

replacing its smallest eigenvalues with a larger, minimum

eigenvalue. The cost is less precision in the final results

since we are decreasing the

precision of the input y data. This is a conservative move, but numerical

stability is worth the trade off. The listing shows that 3 eigenvalues are

modified when svdcut=1e-12 (see entry for svdcut/n); no

eigenvalues are changed when svdcut=1e-19.

The SVD cut is actually applied to the correlation matrix, which is the

covariance matrix rescaled by standard deviations so that all diagonal

elements equal 1. Working with the correlation matrix rather than the

covariance matrix helps mitigate problems caused by large scale differences

between different variables. Eigenvalues of the correlation matrix that are

smaller than a minimum eigenvalue, equal to svdcut times the largest

eigenvalue, are replaced by the minimum eigenvalue, while leaving their

eigenvectors unchanged. This defines a new, less singular correlation matrix

from which a new, less singular covariance matrix is constructed. Larger

values of svdcut affect larger numbers of eigenmodes and increase errors

in the final results.

The results shown in the previous section include an error budget, and it

has an entry for the error introduced by the (default) SVD cut (obtained

from fit.correction).

The contribution is negligible. It is zero when svdcut=1e-19, of course,

but the instability caused by the ill-conditioned covariance matrix in

that case makes it unacceptable.

The SVD cut is applied separately to each block diagonal sub-matrix of the correlation matrix. This means, among other things, that errors for uncorrelated data are unaffected by the SVD cut. Applying an SVD cut of 1e-4, for example, to the following singular covariance matrix,

[[ 1.0 1.0 0.0 ]

[ 1.0 1.0 0.0 ]

[ 0.0 0.0 1e-20]],

gives a new, non-singular matrix

[[ 1.0001 0.9999 0.0 ]

[ 0.9999 1.0001 0.0 ]

[ 0.0 0.0 1e-20]]

where only the upper left sub-matrix is different.

lsqfit.nonlinear_fit uses a default value for svdcut of 1e-12.

This default can be overridden, as shown above, but for many

problems it is a good choice. Roundoff errors become more accute, however,

when there are strong correlations between different parts of the fit

data or prior. Then much larger svdcuts may be needed.

The SVD cut is applied to both the data and the prior. It is possible to

apply SVD cuts to either of these separately using gvar.regulate() before

the fit: for example,

y = gv.regulate(ymod, svdcut=1e-10)

prior = gv.regulate(prior, svdcut=1e-12)

fit = nonlinear_fit(data=(x, y), fcn=f, prior=prior, svdcut=None)

applies different SVD cuts to the prior and data.

Note that taking svdcut=-1e-12, with a

minus sign, causes the problematic modes to be dropped. This is a more

conventional implementation of SVD cuts, but here it results in much less

precision than using svdcut=1e-12 (giving, for example, 2.094(94)

for E1/E0, which is almost five times less precise). Dropping modes is

equivalent to setting the corresponding variances to infinity, which is

(obviously) much more conservative and less realistic than setting them equal

to the SVD-cutoff variance.

The method lsqfit.nonlinear_fit.check_roundoff() can be used to check

for roundoff errors by adding the line fit.check_roundoff() after the

fit. It generates a warning if roundoff looks to be a problem. This check

is done automatically if debug=True is added to the argument list of

lsqfit.nonlinear_fit.

SVD Cuts and Inadequate Statistics¶

Roundoff error is one reason to use SVD cuts. Another is inadequate

statistics. Consider the following example, which seeks to fit

data obtained by averaging N=5 random samples (a very small

number of samples):

import numpy as np

import gvar as gv

import lsqfit

def main():

ysamples = [

[0.0092441016, 0.0068974057, 0.0051480509, 0.0038431422, 0.0028690492],

[0.0092477405, 0.0069030565, 0.0051531383, 0.0038455855, 0.0028700587],

[0.0092558569, 0.0069102437, 0.0051596569, 0.0038514537, 0.0028749153],

[0.0092294581, 0.0068865156, 0.0051395262, 0.003835656, 0.0028630454],

[0.009240534, 0.0068961523, 0.0051480046, 0.0038424661, 0.0028675632],

]

y = gv.dataset.avg_data(ysamples)

x = np.array([15., 16., 17., 18., 19.])

def fcn(p):

return p['a'] * gv.exp(- p['b'] * x)

prior = dict(a='0.75(5)', b='0.30(3)')

fit = lsqfit.nonlinear_fit(data=y, prior=prior, fcn=fcn, svdcut=0.0)

print(fit.format(True))

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

This gives a terrible fit:

Least Square Fit:

chi2/dof [dof] = 4.4e+03 [5] Q = 0 logGBF = -10844

Parameters:

a 0.77794 (26) [ 0.750 (50) ]

b 0.296452 (32) [ 0.300 (30) ]

Settings:

svdcut/n = 0/0 tol = (1e-08*,1e-10,1e-10) (itns/time = 4/0.0)

The problem is that the small eigenvalues of the fit data’s correlation matrix are badly underestimated when we have only a small number of samples (compared with the number of data points being fit). Indeed the smallest eigenvalues vanish (exactly) when the number of samples is smaller than the number of data points.

An SVD cut is needed. We use gvar.dataset.svd_analysis() to estimate

the appropriate size of the cut (by means of a bootstrap simulation that

identifies

the eigenmodes of the correlation matrix that are poorly estimated from

our data sample). To use it we replace the line

y = gv.dataset.avg_data(ysamples)

in the code by

s = gv.dataset.svd_diagnosis(ysamples)

y = s.avgdata

and set svdcut=s.svdcut in the call to the fitter. The result is

the following (excellent) fit:

Least Square Fit:

chi2/dof [dof] = 0.38 [5] Q = 0.86 logGBF = 53.598

Parameters:

a 0.74338 (29) [ 0.750 (50) ]

b 0.292480 (42) [ 0.300 (30) ]

Settings:

svdcut/n = 0.0028/3 tol = (1e-08*,1e-10,1e-10) (itns/time = 5/0.0)

The SVD cut is set to 0.0028 here and modifies 3 of the 5 eigenmodes in the

correlation matrix. Generally one needs an SVD cut unless there

are many more samples than data points — 10 or 100 times as many.

See the discussions in Goodness of Fit and Fit Residuals and Q-Q Plots for further analysis of this example.

lsqfit.nonlinear_fit will apply an SVD cut if keyword parameter

svdcut is set. Another way to implement SVD cuts is using

gvar.regulate() to modify the fit data before it is fit.

y has Unknown Errors¶

There are situations where the input data y is known to have

uncertainties, but where we do not know how big those uncertainties are.

A common approach is to infer these uncertainties from the fluctuations

of the data around the best-fit result.

As an example, consider the following data:

x = np.array([1., 2., 3., 4.])

y = np.array([3.4422, 1.2929, 0.4798, 0.1725])

We want to fit these data with a simple exponential:

p[0] * gv.exp( - p[1] * x)

where from we know a priori that p[0] is 10±1 and

p[1] is 1±0.1. We assume that the relative uncertainty in

y is x-independent and uncorrelated.

Our strategy is to introduce a relative error for the data and to vary

its size to maximize the logGBF that results from a fit to our

exponential. The choice that maximizes the

Bayes Factor is the one that is favored by the data. This procedure

is called the Empirical Bayes method.

This method is implemented in a driver program

fit, z = lsqfit.empbayes_fit(z0, fitargs)

which varies parameter z, starting at z0, to maximize

fit.logGBF where

fit = lsqfit.nonlinear_fit(**fitargs(z)).

Function fitargs(z) returns a dictionary containing the arguments for

lsqfit.nonlinear_fit. These arguments are

varied as functions of z. The optimal fit (that is, the one for which

fit.logGBF is maximum) and z are returned.

Here we want to vary the relative error assigned to the data values,

so we use the following code, where the uncertainty in y[i] is set

equal to dy[i] = y[i] * z:

import numpy as np

import gvar as gv

import lsqfit

# fit data and prior

x = np.array([1., 2., 3., 4.])

y = np.array([3.4422, 1.2929, 0.4798, 0.1725])

prior = gv.gvar(['10(1)', '1.0(1)'])

# fit function

def fcn(x, p):

return p[0] * gv.exp(-p[1] * x)

# find optimal dy

def fitargs(z):

dy = y * z

newy = gv.gvar(y, dy)

return dict(data=(x, newy), fcn=fcn, prior=prior)

fit, z = lsqfit.empbayes_fit(0.001, fitargs)

print(fit.format(True))

This code produces the following output:

Least Square Fit:

chi2/dof [dof] = 0.59 [4] Q = 0.67 logGBF = 7.4834

Parameters: